Reading the Bible Amid the Culture Wars

When we come to the gospels, we meet a nearly nonstop array of the crossing of barriers. Jesus eats with sinners (as defined by the culture as much as the Law itself). He touches the “unclean” (defined by the pious) and welcomes them back into the people of God. Tax collectors join the disciple band along with Zealots. Women are recognized and sinners forgiven. Regarding consideration of cross-cultural relationships, it is a problem of where to begin.

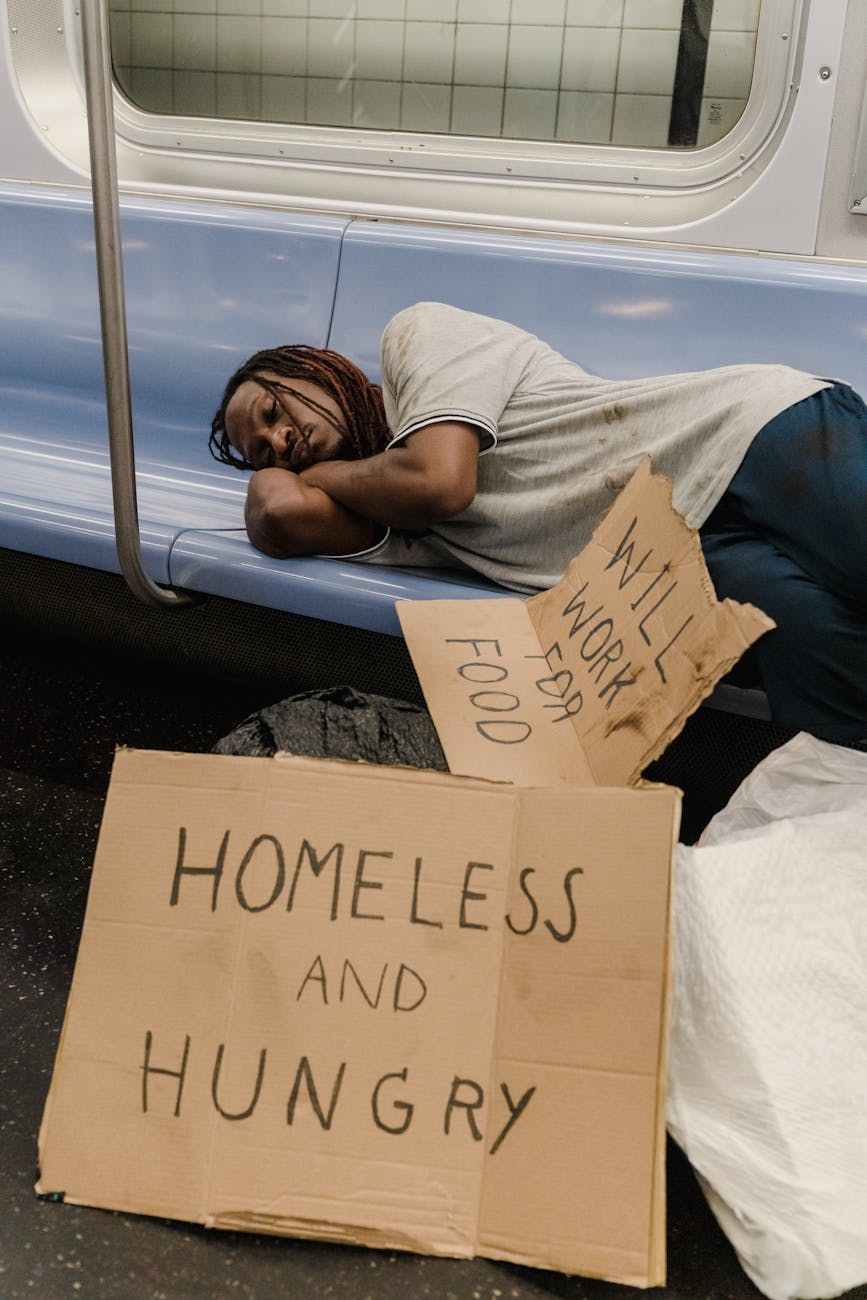

The welcome of the outcast, the stranger, the sick and the downtrodden is a feature of the ministry of Jesus. The demon-possessed are made whole again and the blind to see. His example both sets a template for the Kingdom followers who would be his disciples as well as stirring his opponents to furiously seek his death. For my purpose, I will focus on one story, the so-called “woman at the well,” in Samaria.

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

As we investigate our hearts, we may discover that, just as Jonah did, we harbor resentments, misunderstandings or cultural attitudes as we meet others. Once we have faced the truth that our negative attitudes toward others do not please the God of Jesus in the gospels, we still must do something about it!

Jesus shows us the way. In the wonderful story of the woman at the well, we see Jesus’ example of crossing the boundaries of misunderstanding. When Jesus comes to the well and asks for water, the woman says in John 4:9, “’How is it that you, a Jew, ask a drink of me, a woman of Samaria?’ For Jews have no dealings with Samaritans.” That single statement in John 4:9 contains centuries of bitter history.

This may be hard for us to see because we often focus more on the personal situation of the woman. We tend to see her story as the “toxic history” to be overcome. We marvel at the power of God’s love to cut through the contradictions of a woman who had had five husbands and now was living with someone who was not her husband. This passage has been meaningful for us to talk about evangelism and encouragement for those whose lives are disasters.

There is more here, however. We might also learn to understand that human beings are often caught in toxic history not of their making.When the Jews returned from exile in the Persian period, 538-332 B.C., this provoked envy on part of Judah’s neighbors, the Samaritans. After 722 BC, Israelites left in the north intermingled with foreign settlers (2 Kgs 17). The Samaritans were therefore not recognized as true Israelites.

At first Samaritans continued to go to Jerusalem to worship, but eventually they sought their own place of worship. This explains their common scripture but different places of worship. During the domination of Alexander the Great, the Samaritans received permission to build a temple on Mt. Gerizim.

The hatred between the groups only increased when, in 128 B.C., the Jews under John Hyrcanus destroyed the Samaritan temple. Though it was not rebuilt, they clung to the place as holy even until today where they observe Passover.

Samaritan was a Jewish term of abuse. We see in John 8:48 that it is applied to Jesus as an ethnic slur. Jesus does two remarkable things which show us the way. First, he intentionally enters relationship with the woman and with the Samaritan people. We miss the cross-cultural significance of Jesus’ trip through Samaria. John tells us, “He had to pass through Samaria.” Some of his contemporaries might have responded, “I would travel out of my way to avoid going there!” Jesus faces the difficulties between his own people and these alienated ones.

Second, Jesus probes the misunderstandings that exist between the Samaritans and the Jews. As he usually does, Jesus reveals the limitations of their cultural concepts and replaces them with the higher calling of the kingdom of God. “The hour is coming, and now is, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for such the Father seeks to worship him” (John 4:23). Until our priorities are right, we will still be slaves to the limited views of our own group and personal biases. God is greater than all the local claims of human groups.

Now we see the parable of Good Samaritan (Lk 10:30-37) and the Samaritan leper (Lk 17:11-19) in a different light. Jesus calls his hearers’ ancient assumptions into radical question.

Eventually, we know that the early Christian church also made this leap to receive the Samaritans (Acts 8:4-25). Jesus was transforming the past when he “had to go to Samaria.” He called into question six centuries of competition and resentment. He destroyed the justifications for their separation and declared that in him a new possibility for fellowship existed.

We often harbor secret misconceptions of others and are rarely honest or trusting enough with one another to “lay them on the table” and see them for what they are. When we do, however, Christ can transform them, enable us to forgive and let go so that we might take up life and fellowship with others in a new way.

Furthermore, when we minister to others in the name of God, we are often dealing not merely with personal circumstance, but also the long and painful social scars of history and culture. It is essential to understand the humility and wisdom required to tread in such places.

The word “Samaritan” is most familiar to readers of the Bible in the so-called parable of the Good Samaritan, remembered in Luke 10. Jesus is asked by a scribe, an expert in the Law, “Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” Jesus replies, “What is written in the Law?” he replied. “How do you read it?”

He answers Jesus, “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind’ and, ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’” Jesus then commends him. “You have answered correctly. Do this and you will live.”

His questioner was not prepared for Jesus to commend him. He was prepared for a disagreement. So, the text records, “he wanted to justify himself, so he asked Jesus, ‘And who is my neighbor?’”

Now Jesus tells a story. You probably know it. A man was traveling on the road between Jericho, near the Dead Sea, and Jerusalem. It was a steep and dangerous journey, a crime-ridden area frequented by robbers. They attack the man, rob him, and leave him to die.

Then, in order, come a priest and a Levite, both symbols of Jewish piety and importance. Seeing a man who may be dead (touching which would bring them into contamination, delaying their ability to carry out their duties at the Temple), they pass by on the other side. Jesus’ listeners might have thought, “I can understand it. It’s a scary situation.” But then, along comes a Samaritan. He stops, cares for the man, takes him to an inn and arranges for his care and pays for it.

“Now, which one was the neighbor?” Jesus has turned the question back on his questioner. The dorm bull session has turned into a moral crisis. He answers, “The Samaritan.” We do not know his tone of voice.

Not long ago, the Vice President famously got into a theological argument with the Pope and all of us who do this for a living. He stated that “loving our neighbor” doesn’t mean the whole world. It should prioritize our loved ones, our own “people,” and not necessarily have to attend to every suffering in the world. He is a very recent convert to Catholicism, and apparently favors traditionalists. (I am reminded of the late Jaroslav Pelikan’s observation that we are to keep the living faith of tradition rather than the dead faith of traditionalism.)

“Traditionalists” tend to close themselves off from the idea that God can ever do something they haven’t already heard about. Mr. Vance was wrong about Jesus and the Bible. Now, he had a point that you can’t love the whole world and neglect your nearest neighbor—family, friends, your “people,” as we might say. But if that becomes an excuse for neglecting those who are different, trapped in the collective toxic mess human systems and prejudices have created, he is wrong.

If there is a way to love someone in need on the other side of the world that is within our power to do, it is upon us to do it, at least if we want to call ourselves by Jesus’ name. We can donate to a go fund me for someone we never met. We can feed refugees on the other side of the world. We can work to repair damage done to others that was not necessarily our own personal responsibility. We take it on as we “take up the cross and follow Him.”

Conversely, if we neglect the suffering of the world by politics of selfishness or lifestyles of greed, who are we? It is not a simple matter, of course. Of course, issues are complex. But these two actions Jesus gave us—an intentional stepping over a line of division at a well, talking to a \woman considered “out of bounds,” and a story about a man who came the other way, toward a man in need whose people despised him and thought they had history on their side, then it is Jesus we must answer to, not social media or our own rationalizations.

No one gets to “rewrite history.” We might try, but what has transpired, the wounds, injustices, and cruelties we have wrought to one another, live on, whether we lie about it to ourselves or not. Either we repent and make amends, or we continue to live the damage to each other. Culture wars, it seems, are simply one more version of all wars, where we insist, while killing one another in body or soul, that there must be “winners and losers” and nothing else. The result, tragically, is cosmic lostness.